A Landscape Rich In People and In Life

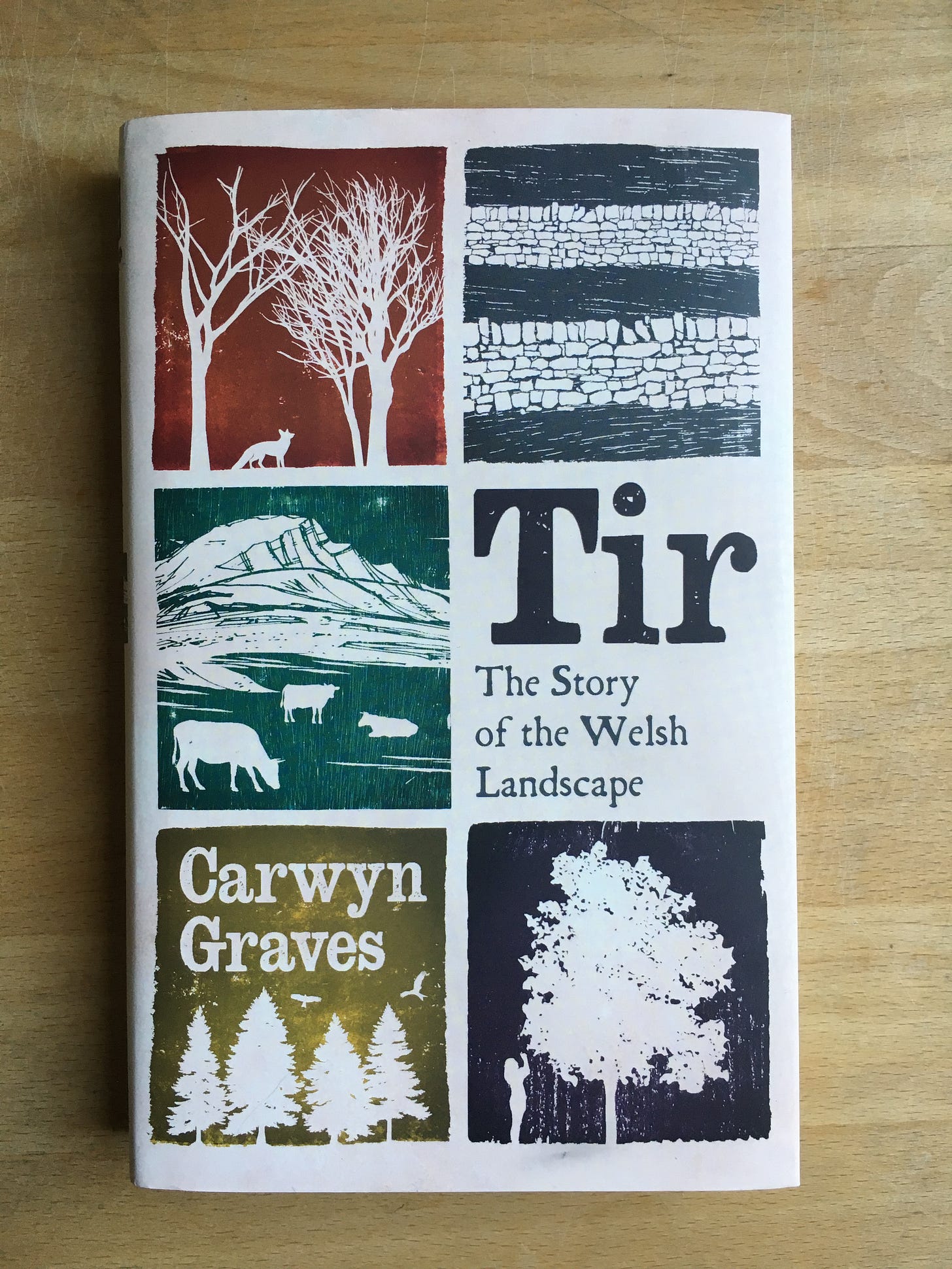

A Review of 'Tir: The Story of the Welsh Landscape', a book which has plenty to say concerning the current Rewilding debate.

In the United Kingdom, we are blessed with some of the most extraordinary countryside: rich in beauty and teeming with heritage. From the rugged and romantic fells of the Lake District to the verdant, secluded valleys of Wales, we are truly, greatly blessed. Blessings, though, are often tainted with a curse; our treasured landscapes are no exception. Though they may seem idyllic — and they often are — probe even a little underneath the surface and one finds division and conflict lurking in the shadows of many of these “idyllic” places. From time to time, a variant of this division comes to a head on the toxic spaces of the ‘Twittersphere’ as an intense, and at times, vitriolic debate. Two firmly entrenched sides shout at each other from either side of the proverbial hedge1: farmers versus conservationists; rural dwellers versus rewilders. One side sees the need for the land to produce abundant food as primary; the other claims precedence for the return of trees, megafauna, and microfauna, en masse, to address the twin crisis of biodiversity loss and climate change. Both sides are well-armed with valid arguments and legitimate concerns, but seem unable to come to a compromise, let alone an agreement. Thus, the divisions in the countryside persist and fester.

And while the battle rages on in the virtual spaces of social media2, the physical land continues to suffer from the twin curses of neglect and abuse. Bracken slowly continues its onward march of domination in the uplands, and the ecological “no-man’s lands” of intensive monoculture and improved grasslands conquers ever more of the lowland’s fields. Division leads to degradation.

One must ask, is there another way? A middle ground, perhaps, which avoids the extremes of the “exclusive productivity-driven mindset”3 of some farmers, and the “let it all revert to nature” mindset of some rewilders? A middle ground that provides a nuanced and thoughtful understanding of the landscape, respecting complex histories, unique heritage, and differing demands, and where both ‘cultural-diversity’ and biodiversity are cherished and protected? Carwyn Graves book Tir: The Story of the Welsh Landscape offers a convincing middle ground which does just that.

Carwyn’s main thesis is simple: the Welsh landscape that millions love and visit each year, is a deeply peopled landscape: the product of centuries, even millennia, of human interaction with nature. This mutually beneficial interaction has resulted in a rich wealth of biodiverse habitats — some unique to Wales — that have been created by traditional agricultural management practices passed down through the centuries. The abundance of biodiversity in these remnant habitats4 is because of humans and not in spite of them — as modern environmentalist dogma would have us believe. The necessary conclusion deduced from this is that if we want the rich biodiversity to persist, then humans must remain an integral part of the landscape and be enabled to continue to practice traditional and sensitive ways of interacting with the land.

This becomes all the more apparent when we consider — as Carwyn astutely observes — that it is futile to try to turn back the time and “return” the landscape to a pre-human “natural state”, for the influence of humans upon the landscape has occurred for millennia. Humans have left an indelible mark upon the Welsh landscape, so much so that removing humans and their management is in itself an unnatural act5 akin to removing a keystone species from a habitat that has come to depend on it. Both man and nature are thus essential and cannot be separated. Remove one from the equation and degradation to the land will be sure to ensue, whether this be the intensification and commodification of the landscape when nature is removed, or the afforestation and “brackenificiation” of unique semi-natural habitats if the land is abandoned by people.

Both these outcomes would be an abject tragedy. The harm caused by the intensification and commodification of the landscape is easy to perceive. The powerful twin forces of industrialisation and fossil fuel-based intensive agriculture have led to Wales being “one of the most nature depleted nations on earth”6. The impetuses behind these forces are commodification and extractivism of the products of the land, all to fuel our growth-based economies. The harm caused by land abandonment is perhaps more difficult to perceive, especially when you have some environmentalists proclaiming “This is just what the land needs.”7. To understand why this is a tragedy, one needs to understand the Welsh landscape as a fundamentally human-managed landscape, with much of its biodiversity dependent on this management’s persistence. This integral understanding is what Carwyn’s book skilfully demonstrates — time and time again.

To prove his thesis, Carwyn visits seven different habitats, ranging from woodlands (coed8) to heathlands/bogs (rhos), on his journey around Wales, to listen and to learn from the men and women who have committed to caring for these precious places. Along the way, we meet men such as Gareth, a traditionally minded farmer who resisted the pressures of intensification and has thus preserved a remarkable (coed) hay meadow teeming with insects and a “pastel profusion” of wildflowers9. Simply put the landscape exists in its abundant glory because of him. We also are introduced to women such as the remarkable 87-year old Linda of Cherry Orchard Farm who takes care of an ancient orchard (perllan) where rare species of invertebrate, some of which are likely to be found nowhere else in Wales, thrive alongside precious heirloom varieties of apples and perry pears, whose flavours far exceed anything that can be purchased in the supermarket. These are just two of the many examples of hidden farmers in the book: men and women who labour faithfully outside of the public eye, come rain or shine, to produce beautiful, rich, and sustainable goods from the lands they are entrusted with. Carwyn has rendered an immense service to these faithful men and women in letting their voice be heard and in allowing their loving, caring, and skilful example to be witnessed — and hopefully emulated.

As well as their faithful and skilful labour, something which was readily apparent with all of the farmers and land managers that Carwyn met was their love for the land and its wildlife. Indeed, this rooted and place-based affection was the driving force behind their dogged persistence in undertaking traditional management in the face of intense modernising pressures. It is true, then, and not mere sentimentalism, to say that behind each beautiful and diverse habitat or landscape (both in Wales and where you live) is love. The rich biodiversity, complex habitat integrity, and unique aesthetic and cultural beauty present in these loved places all flow from this. Wendell Berry was right after all, it truly does “all turn on affection”10.

It is not only biological diversity that these ancient lands are rich in. Tir is a book abounding in poetry and verse, all in Welsh (though thankfully translated), which appear to have overflown from the Welsh rural folk down throughout the centuries. Not only does this literature give us a unique insight into the natural history of Wales (and the historical geographic extent of now much diminished habitats), but the literature and language add an additional layer of meaning upon the landscape and are thus integral for our accurate understanding of it. Perhaps most importantly, the language and literature highlights landscape features that might otherwise have remained hidden or overlooked. Ffridd, for instance, is the name for a “lightly wooded mountainside” habitat unique to Wales, differentiating it from similar habitats. If this landscape was termed simply as scrub or “transitional habitat” the unique habitat structure and its faunal and floral communities might otherwise be overlooked. Further, the frequent references to Ffridd in medieval poetry (such as a verse referring to Ffridd as “golden places”) highlights how for centuries these places have been valued as special, cherished places, deeply ingrained and celebrated within in the Welsh collective heritage and are thus worthy of our attention and affection today.

That the literature and cultural identity of Wales is deeply intwined with nature, along with the traditional management which has preserved it, presents a possible point of dialogue and agreement concerning the farming-rewilding debate. It is deeply ingrained within the Welsh psyche that the land should be farmed, but the Welsh are also passionately proud of their heritage, language, and culture. Showing how much of this language is tied to the land, traditional management practices, and unique habitats is one way of showing Welsh farmers the importance of the habitats they steward, which they may have neglected in their overarching pursuit of food productivity.

Those on the other side of the “hedge” can also learn a thing or two. Reviving the language and traditional culture among the people of Wales, both urban and rural, will, perhaps, rekindle an affection for the “peopled landscapes” of Wales. When one considers how infused the language is with traditional agricultural heritage11, a favourable disposition towards farming becomes easier to hold. Thus, being well-versed in the language and its origins may help to sway or soften the stances of rewilders and show that the solution to the biodiversity crisis is not to remove humans from the land, but to enable farmers farm in a more traditional way. This kind of farming created immense biodiversity and beauty in the past and has the potential to do so again. If we let it.

It is not cheap or easy, though, for farmers to farm in this way, especially in a global and interconnected world where they are exposed to brutal cost-cutting competition from abroad. They are in need of our support if they are to farm in this deeply sustainable way12. We can do this through buying from them direct, advocating for local and national policy that supports traditional livelihoods and management, and perhaps, committing to working alongside them. As Carwyn argues, “the cultural framework for the transition to more sustainable and biodiverse farm landscapes lies latent in the Welsh language”. May it be revived.

Conclusion

The twin arguments that Carwyn presents in this marvellous and important book: that traditional management is vital in maintaining biodiversity and that the cultural framework for transition to more sustainable and traditional farming systems is found ingrained in the Welsh language, are arguments and pleas rarely heard in our halls of power or institutions of learning. But they powerful and worthy arguments nevertheless. Tir thus serves as a valuable testament to the immense value of the traditionally minded Welsh farmers in the Welsh landscape and begins to chart out a framework for a convivial future for the land, its wildlife, and its people. May its audience be wide, and its application be extensive.

Additional thoughts and comments

A few closing points that are worth additional mention.

An area of particular strength with the book is its treatment of livestock, showing how integral the presence of livestock is for healthy cultural and biodiverse landscapes. Carwyn’s argument that the habitats in the Welsh countryside are a product of the interplay between “grazing livestock, trees, and human choices”13 is a particularly helpful framework which has relevance across the globe in agrarian-rewinding debates. Tir is also sensitive to the damage that over-stocking can cause to fragile habitats and floral communities but is at pains to show how integral livestock are to the persistence of unique habitats such as Cae hay meadows and Ffridd. Additionally, the book shows that for many traditional habitats, their persistence is best served by the continuation of traditional agricultural management (such as the equilibrium Gareth has maintained on his hay meadows) using livestock, and not by constant conservation management (without livestock) which tries to preserve the habitat in a fixed state.

The book is extensively and exceptionally researched and referenced and digs into the rich storehouses of Welsh literature. Verses, poems, and passages populated the book throughout giving the narrative a sense of timelessness. This is all the more impressive considering Carwyn accomplished all this research through the use of public libraries — which proves that when the motivation is there, this level of research is available to everyone.

If you would like to purchase a copy of Tir: The Story of The Welsh Landscape, consider doing so through Bookshop.org. If you order through this link, you will be supporting local independent bookshops and I will also receive a small commission which will go towards supporting the work I do here on Over The Field.

Tir: The Story of The Welsh Landscape by Carwyn Graves. Calon.

Or cloddiau in Welsh.

The very place where solutions to complex problems such as land management are unlikely to be found. For you can’t fit much nuance and complexity in 280 characters.

Wendell Berry, Quantity Versus Form.

I use remnant as sadly, many of these original traditional habitats have subsequently been lost to the ravages of agricultural intensification in the last 70 years.

Let alone an act that is goes deeply against the grain of the indigenous Welsh belief that the land is to be farmed.

Tir. Carwyn Graves, page 2.

https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/george-monbiot-rewilding-countryside-end-sheep-23999

Welsh.

Tir, page 80.

The title to Wendell Berry’s 2012 Jefferson Lecture.

E.g. the many roots, stems, and terms that derive from traditional agricultural culture.

The Welsh farmers cannot rely on the government for help as Carwyn has shown repeatedly that they are no friend to traditional and sustainable land management.

Tir, page 179.

Thank you for this, Hadden. I'll add this book to my list.

Also, this affection for a land one cultivates and sustains seems to ring resonance with David Kline, Amish farmer who wrote the lovely book Great Possessions.