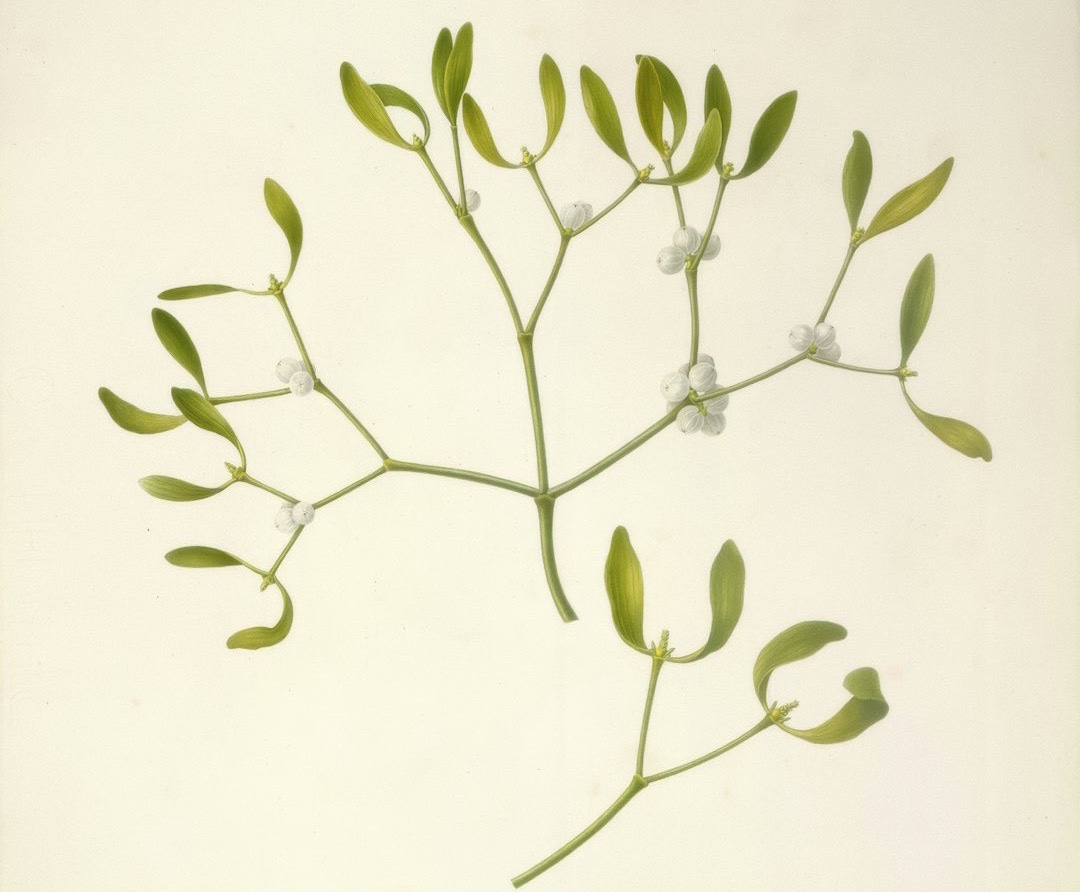

A strange and devious plant stakes its claim high up in the trees; a parasite slowly sucking the vitality out of its giant arboreal host. Each winter, as the leaves descend and the branches of the trees all around are left bare, the parasite is exposed: a circular bundle of matted, evergreen leaves bedecked with tiny white berries that glisten seductively like pearls. The parasite was there all along of course, hidden away in the dense leafy canopy through the long summer months. Winter, though, reveals its presence and exposes it to the predation of man — for winter is the season of Christmastime, and since the Victorian era, Christmastime has been the season for mistletoe.

For any budding naturalist, this peculiar plant offers a veritable feast of intrigue, ecological wonder, and anatomical oddities. Though often referred to as a parasite, strictly speaking it is a hemiparasite.1 Like other plants, its green leaves are photosynthetic, but unlike most other plants this is not the primary means by which mistletoe receives its sustenance. For that, the mistletoe steals from its arboreal host; an apple tree is its particularly favoured target — but most other broadleaved trees will do just fine. Latched on to the branches of the unsuspecting tree, the mistletoe sends out its ultra-fine haustorium, (a root like structure that penetrates the bark) to absorb nutrients and water from the host tree. The mistletoe becomes wedded literally one flesh with its host, dependent upon its partner’s continual compelled “benevolence” in sickness and in health, till death do us part.

The infected tree is utterly defenceless against this spreading parasite. And as the picture below vividly demonstrates, mistletoe can very well conquer the entire tree, weakening its branches to such an extent that a mere gust of wind can spell disaster, not only for the tree but for any unsuspecting human walking beneath.

“But how does the mistletoe get up there?” one may ask. It is a very good question. And for the naturalist, this is where things get very interesting indeed. At least, I think so.

Mistletoe is renowned for its pearly white berries. Though toxic to humans, these berries are a tantalising treat for two British birds in particular: the mistle thrush and the blackcap.2 These two species of songbird are the comrades in arms that aid and abet the spread of this parasite to new trees. Without them, the mistletoe would struggle to perpetuate. Dependent on its host and dependent on these birds, it is a very dependent plant indeed, this mistletoe is.

Let’s start with the mistle thrush. This is a large, mottled brown and beige member of the thrush family, the bulkier cousin of the famous song thrush and in my experience, it is the rarer of the two species. As the name suggests, the mistle thrush loves mistletoe berries, so much so that we have named the species after them. Once a mistle thrush discovers a clump of mistletoe, it voraciously defends its “pearls without price” from any intruder, dive bombing them with a violence that seems almost excessive — almost like a missile. Treasures can bring out the worst in us I suppose.

Being a relatively big and bulky songbird, the mistle thrush consumes the berries whole, and this seemingly insignificant piece of information is a vital piece in the puzzle of how the mistletoe colonises new trees. Once it has had its fill, the thrush flies off to a suitable perch, and given time, nature calls. It defecates the seeds in a white, sticky gloop that, hopefully for the mistletoe, will land, and crucially stick, on another branch a good distance away from the parent plant. Thus, a pioneering bridgehead is established in new and uncharted territory in the canopy of the latest arboreal victim, for this seed needs no soil in order to grow, only the bark of a branch is required.

The blackcap is an altogether different accomplice for the mistletoe — and perhaps the preferred partner in crime at that. The blackcap, being a warbler, is a much smaller songbird than the mistle thrush and is incapable of swallowing the mistletoe berries whole. Instead, it deftly plucks the berries from the boughs, and bites down with its beak into the white flesh. This releases the mistletoes secret weapon: the flesh of the berries is extraordinarily sticky and viscous, so much so that the berry is the gold standard of viscosity; it is, in fact, its definition, for Viscum album — the Latin name for mistletoe — is the etymological origin of our word “viscous”.

Though the blackcap thoroughly enjoys the sweetness of the berry, its beak is now covered with a sticky, seed-laden residue; a mighty and embarrassing inconvenience. The only option available to save face is for the messy eater to wipe its beak on a nearby branch — a woody napkin — thus depositing the seed safely and efficiently on a fresh branch for the mistletoe to parasitise. This phenomenon helps explain why individual trees are often laden with ten or twenty mistletoe boughs, for the blackcap is unlikely to travel far to clean its sticky bill.

The blackcap may also be the saviour of this peculiar plant. If you look at the distribution map for the mistletoe in Britain, you can clearly see the heartland for the plant is the west country of England. Climatic and geographic reasons help to explain this hotspot of abundance, but another reason is the preponderance of traditional orchards that grow here in what is Britain’s premier apple growing region. That is, this was the case. Now, under the destructive pressures of agricultural intensification, these traditional orchards are disappearing at a rapid rate, grubbed up to make way for more efficient, streamlined orchards that are perfect for machines, but terrible for wildlife. The favoured habitat of the mistletoe is vanishing right before our eyes. The parasitic nature of this plant is also no help for its survival in this harsh, dog-eat-dog economic climate. By its very nature, mistletoe competes with its apple tree hosts, harming their ability to yield abundant fruit. Unsurprisingly, this is a crime worthy of capital punishment in the modern, hyper efficient orchard.

To the rescue, enter in the blackcap. As our climate warms, this species has largely forsaken flying south in the winter to warmer climes and has decided instead to persist all year round in the British countryside. As mistletoe berries appear in winter, the plant has attained this new helper, whose efficient and effective transportation of seeds has furthered the increase in abundance of mistletoe at a time where the plant has needed help the most. Thus, we have the humble blackcap to thank that come Christmastime, the countryside continues to abound with a ready supply of mistletoe to satisfy our curious festivities. Perhaps, then, the blackcap rather than the robin red breast is the bird we should celebrate the most at Christmas.

Though I personally find the ecology of the mistletoe the most fascinating thing about this most peculiar plant, ecology sadly doesn’t fascinate everyone. But that is ok, because ecology is not why the prime reason why mistletoe is so renowned. No, it has Charles Dickens to thank for that.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Over the Field to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.