All That We've Lost

On the tragedy of 'absolute loss' in the countryside

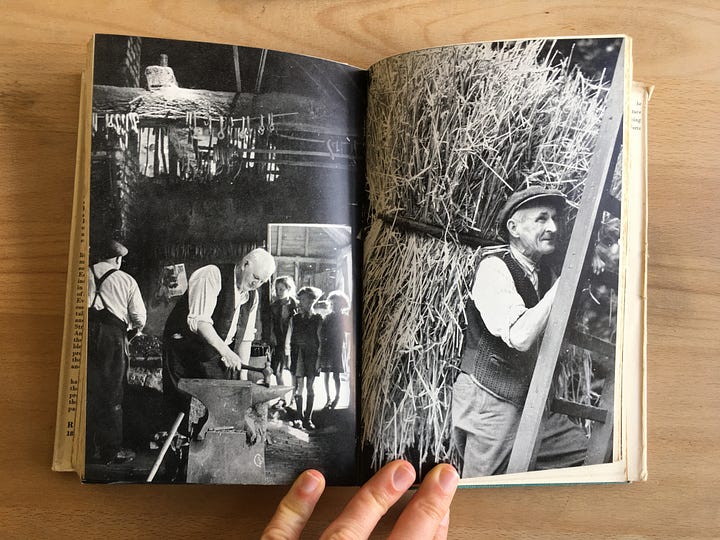

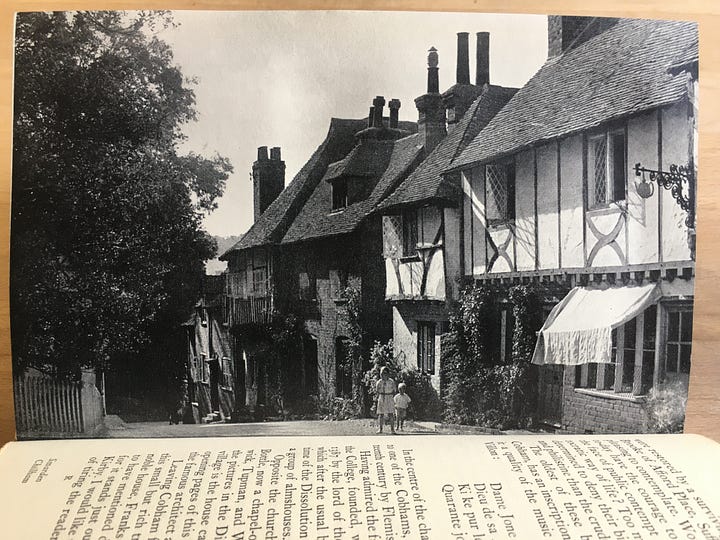

I enjoy collecting old books. Not any old books, mind you, but good old books, written by folk who possessed a deep love for the British countryside and who combined their passion with an expert knowledge of the wildlife, people, and traditions that called the countryside home. These are the best old books, and the cream of the crop amongst them feature a rich selection of black-and-white photographs depicting how Britain used to be in all its agrarian glory.

Though I find reading these books a great delight, it is at the same time a rather painful experience. Painful in that I am made aware of all that Britain has lost — and all that is never coming back. Fields full of lofty hayracks, majestic Shire Horses working the plough, flat-capped farmhands with their broad smiles, and abundant hay meadows full of wildflowers — all these, and much more, once constituted the agrarian soul of Britain, an indispensable part of our heritage. That is, until we determined that economic efficiency trumped everything — and thus decided all this agrarian heritage was, in fact, dispensable.

Nostalgia — that much maligned sentiment — naturally wells up within me as I linger over the monochrome photographs and poetic prose that portray the beautiful scenes my eyes will never witness. I find myself wishing I could be transported back to these ‘good old times’ when agrarianism flourished, when farmland wildlife was abundant, and when society seemed to care about the appearance of our rural places.1 “Why are things not like this now?”, I lament... And then I remember that I am part of the problem.

Lost is a terrible word. A fearsome word, even. It means that something good is missing, gone, or destroyed. A wedding ring falls into the long grass unnoticed; a marriage denigrates into divorce; a beloved young spouse dies prematurely. Though the severity of the loss across these examples differs drastically, a sense of profound pain is palpable in them all. Loss is always tragic.

With regards to many lost things, however, there is a hope that remains: the hope of being found. Occasionally, this happy ending does happen, and the sense of relief it brings is, at times, euphoric — which goes to show just how deeply loss can affect us. Rightly, then, is there cause for lavish celebration when the “lost” becomes the “found”.

There is, though, another kind of loss that stalks the shadows of our lives. It is when that which is lost is never coming back, no matter how hard the seeking or the striving. This is the “lost” that will never become the “found”. All of us will encounter this form of irreversible and permanent loss at some stage in our lives; the inevitability of death ensures this.

So much of the loss that has affected our countryside in Britain can be classed under this second and utterly tragic kind of loss. Extinction (or expatriation) of charismatic species and the destruction of ancient habitats are the two most notable forms of what I term “absolute loss” that have blighted our countryside as of late. These are big and blatant losses, losses that we sit up and take notice of, and losses which feature prominently in our collective laments on social media (before, that is, we all go back to doing and supporting the very same activities which caused the losses in the first place).

But what may go unnoticed are the small and local losses occurring daily around us. The loss of an old oak tree, the demise of a population of rare but diminutive wildflowers, and the subtle but ongoing infill and pollution of a local, species-rich pond. Absolute loss is occurring all around us. Open your eyes; seek and you shall sadly find.

It would be wrong to state that all instances of absolute loss in the countryside are caused by man. Habitats naturally change over time — and sometimes collapse — and death will eventually come to all creatures. Even extinction is, in sense, a natural and expected phenomena — though not at the rates we are currently observing. However, though loss is natural, much of the most destructive and brazen forms of absolute loss occurring in our countryside are directly caused or mediated by man. Widespread introduction of invasive species, the bulldozing of habitats, the pollution of fields and rivers, the overhunting of wildlife — these destructive events and the losses they caused were entirely avoidable. Yet we pressed the button anyway.

As alluded to before, so much of the absolute loss we are causing is because we have prioritised the economy well above the countryside. We are building our GDP whilst losing what we have been entrusted to steward: Building Britain’s economy at the expense of Britain’s soul. Now there is a slogan that might shame our politicians — who are permitting, if not driving, much of the desecration of the countryside — into action. They are making a Faustian bargain, and one they will come to bitterly regret. For the sake of a bit more prosperity and another term in power, our politicians and business leaders are toying with an inheritance that is not theirs to destroy. Their legacy will not be their fortunes, neither will it be the economic growth they have presided over. No. Their legacy will be the destruction of the countryside and they will they be known as the ones who ripped the soul out of a nation and replaced it with a hollow warehouse full of mass-produced goods — the epitome of triviality. A tragedy of tragedies.

What should we do in the face of the continuing loss of beauty, meaning, and richness in the countryside — a tragedy we are all somewhat implicated in? It is to do what any sane person would do: we weep. We must let the gravity of the situation affect us to the core of our being. But weeping is in vain unless it also moves us to take costly action for the sake of what we love.

For the sake, then, of our countryside and the future generations who will inherit it, we ought to protest vigorously against its on-going desecration, we must commit to disentangling ourselves from the forces that are responsible for its ongoing destruction, and we should support financially those small farmers, conservationists, and politicians who are endeavouring to protect and revive what is left of its beauty.

Ultimately, however, we must recognise that unless we inspire the general population to once again care for our countryside, all hope is lost.2 There is only so much good a small group of people can do — no matter how committed they may be. If the rest of the nation is content to allow — for the sake of ever higher economic growth, personal prosperity, and personal comfort — the ongoing destruction and degradation of the countryside, then all hope is absolutely lost.

We must find ways of making the average person in our nation care deeply about nature and rural places — deeply enough that they are prepared to make sacrifices for the good of the countryside. And that is where exposing folk to those old agrarian books may come in of use — as well as getting folk out and about in the countryside and engaged in it with their bare hands: clasping billhooks, binoculars, and foraging baskets.3 By witnessing the memory of all that we have lost, and by becoming deeply involved with all that we have left, we might just, as a nation, muster up the willpower to stem the tide of absolute loss that is buffeting and destroying our precious countryside. One can only hope.

I began this piece with a photograph of a tree. It was no ordinary tree. It was one of the nation’s most beloved trees; a picture-perfect example of what a tree ought to look like, situated in what can only be described as a geometrically perfect setting. This was the famous Sycamore tree of Sycamore Gap.

You may have noticed that I have used an ominous word to describe this tree: “was”. This can only mean one thing — this beautiful tree is no longer standing. And that is correct. Its demise — an act of gross stupidity by two chainsaw wielding thrill seekers in the dead of a stormy night — is permanently seared into our national collective memory. Every time we view a photograph of this picture-perfect tree we let out a deep sigh: the Sycamore tree of Sycamore Gap is absolutely lost. Though the stump remains and a new tree is sprouting from the old, it will never look the same way again. The loss of beauty, at least, is absolute.

For a brief moment in the aftermath of the felling, we as a nation felt the utter weight of the tragedy, and deep within us stirred the passion never to let this happen again. How could we continue to countenance the loss of beauty in our countryside? How could we let another creature slip into extinction under our watch? How could we replace another ancient woodland with another insipid business park? These questions swirled around in our minds and out onto our Tweets and Notes, causing some of the more hopeful (or naive) among us to wonder whether our collective outrage might just turn into widespread acts of preservation and protection of what is left of the beauty of our countryside.

But then, the inevitable happened. Another day dawned and with it came the next episode of bad news to light up our screens. Our collective lament and rage transfixed itself on another object — such as the brokenness of our economy — and the impulse to mend our fractured relationship with our countryside vanished as quickly as it came.

Some may even say the desire was absolutely lost.

The subject of the ongoing loss of our countryside and what makes it special is one which concerns me deeply and is part of the reason why I write these essays. I hope through my words to inspire others to care deeply for the countryside and the people and creatures who call it home. One of the ways I do this is through my sister publication, The Village Green, which is devoted to showcasing the beauty of the British countryside.

For the next two weeks, all new paid subscribers to Over the Field will also receive a six month complementary paid subscription to The Village Green giving you access to future posts and my growing archive. Thank you for your support.

I am aware this is a rather rose-tinted view of the agrarian heritage of Britain. There were, of course, some significant negative attributes of this time, such as the prevalence of back breaking labour; inter-village parochialism of the worst and most offensive kind; and troubling (and sometimes abhorrent) attitudes towards women.

Roger Scruton, Green Philosophy. Atlantic Books.

Have you watched Jack Hargreaves TV programmes from the 1980s eg "Old Country" . They are a marvellous celebration of the old country ways and knowledge. Ive watched lots on You Tube. . A wonderful man.. I remember one programme where he went in his horse drawn caravan along the old high roads and explained what a high road was... SO fascinating.. you probably know his stuff already but if not you will LOVE it (and it will break your heart) xxxxxx

This reminds me of the loss of the great American prairie and all the wonderful and varied inhabitants of it. Plants, animals, birds, insects, the soil itself. I studied Botany and Plant and Soil Science at Southern Illinois University from 1978-1981 and even then it was down to a few hundred acres. All the species that comprised that great region are gone in the name of mechanized giant monoculture of wheat, corn and soybeans. Hundreds of millions of acres across the whole middle section of our country have been destroyed by greed for grain that mostly goes to beef cattle production for cheap beef. For cheap fast food.

Why? Because in part, prairie grasses produced beautiful deep fertile soils that could produce higher yields per acre of whatever was grown.

The same thing is happening here in the Palouse region of eastern Washington state but they have been better at managing areas for the native species.

But ultimately, there is habitat loss worldwide because of humanity’s demand for more….