Last week, I fell in love with what was once a slum. It may sound rather odd for a “Romantically-Inclined Person” to admit this; slums tend to rank near the very bottom of the list of “beautiful places” and are instead, rather dangerous, unsanitary localities. Certainly, the slums that I have visited in Kenya and South Africa match this description.1 The crucial word, though, in the sentence that begins this essay is “once”. For a slum, this place is no more. Now, tourists of the most fashionable sort fill the old, cobbled streets in this the most picturesque part of Stockholm, the capital city of one of the most “developed” nations on earth. This place I fell in love with is Gamla Stan2.

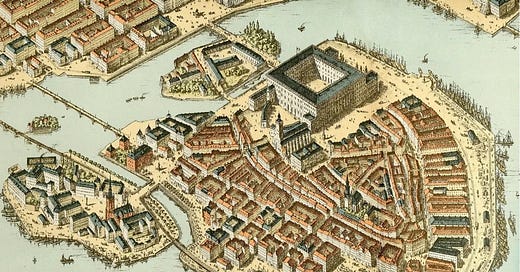

The supposed origins of this remarkable old town are unusual — the stuff of legend. It is claimed that 1000 years ago, the chiefs in the old Swedish capital of Sigtuna were so sick and tired of coming under attack by raiding gangs that they came up with a rather absurd scheme for finding a new home. They hollowed out a log, set some of their precious gold inside, and set it afloat on one of the many waters which cover this part of Sweden. After a journey of three days, the log finally came to rest on the island of Stadsholmen in the Stockholm archipelago. Thus began the story of Gamla Stan, and indeed Stockholm itself.3

It is a story that came perilously close to being cut tragically short. Though once a prosperous medieval city, Gamla Stan fell into disrepute in the late 17th century as the capital city developed into the surrounding archipelago and Gamla Stan was left behind. This small island became a sordid, filthy slum — an eye and nose sore for the emergent Swedish empire. The hawks of modernisation were circling above the filth of the town and one urban architect by the name of Rudberg4 had his sights set on radically refashioning it. This, as most urban regeneration projects do, involved razing all that came before to the ground. His plan was to beautify this relic “left over from the Middle Age’s barbaric way of life”5 along the norms of the Baroque vision. Thankfully, Rudberg’s schemes were defeated by the “small” matter of cost. Thus Gamla Stan, with all its history and latent beauty, was given a reprieve.

Fast forward to the 1970s and Gamla Stan’s reputation improved drastically. Suddenly, the aesthetics of the town were in vogue. Tourists flocked to marvel at the quaint, narrow, cobbled streets lined with ochre-coloured, rustic houses in addition to admiring the King’s palace on the outskirts of the town. The trend has continued to this day with thousands of tourists thronging the veins of the city every day, offloading, as they course through the streets and alleys, their precious dollars, pounds, and Krona to the shop proprietors and inhabitants of Gamla Stan.

Becoming a tourist hotspot can, though, be a curse. Any inhabitant of a hotspot will tell you the peak seasons come with inevitable overcrowding, which can make life unbearable for those who call these places their home. But that is not all. The abundance of tourists in Gamla Stan has led to another rather unfortunate phenomenon. Along the main street, greedy landlords have capitalised on the glut of dollar spending tourists to push up the rents for the shop owners. Traditional, family-owned businesses have been pushed out to be replaced by tacky knick-knack shops — ubiquitous to every honeypot site — selling Swedish flags, t-shirts printed with “I love Stockholm”, and mass-produced modern bric-a-brac that deludes buyers into thinking that they have purchased something “traditionally Swedish”. These places annoy me intensely. So, I sought out the byways and neglected streets of the old town, places that yield many secrets to those who pry.

Prästgatan was one such place. It is a narrow street named after its former priestly inhabitants, that runs directly parallel to the main tourist street of Västerlånggatan. It was here that I fell involve with Gamla Stan. Rustically painted old houses lined the street on both sides, gently rising and falling with the topography of the area. This was a street that conformed to the contours of the place rather than forcing the place to conform to a straight geometric logic. Antique shops selling authentic traditional and historical pieces were to be found hidden away in cellars and old restaurants where local delicacies could be sampled appeared at intervals along this beautiful street. Nestled into one of the walls was a real piece of ancient history: a runestone beautifully and skilfully etched by ancient hands one thousand years ago. This was the real old town — the real Gamla Stan. And even though the main tourist street was in earshot, I had it almost entity to myself. It was bliss.

Perambulating along the narrow, car-free streets gave ample time for reflection. There was something unique about the beauty and charm of Gamla Stan which separates it from other old towns I have visited, something which puts Gamla Stan on another level. As I have meditated on what I saw, I think what makes this place unique is due, in large part to two factors.

Firstly, the beauty here was, in a sense, natural. The colours of the buildings were all either sandstone, ochre, beige, or burnt red — natural colours derived from the earth. On the one hand, the coherence and uniformity of colour over a substantial area provided an aesthetic spectacle. But there are plenty of other places I have been where there is a uniformity of colour which do not draw me into awe. In fact, the uniformity of these places have been dull, depressing even. Why was Gamla Stan different? Partly it is due to the natural colours chosen, but also the paints used provided subtle variations in tone and shade. No two buildings had exactly the same colour — and as the angle of the sun changed throughout the day, so did the colour of the buildings — with the glow in the evening light being particularly spectacular. This ever-changing palate with its subset variations mimics the aesthetic variation we see in nature: the shades of green and brown on the trees are not uniform and neither is the colour of the soils. Mimicking nature’s changing palette made Gamla Stan significantly more beautiful and infinitely more interesting.

The resonance with nature didn’t stop with colours. The buildings themselves, and the layout of the city generally, were full of imperfections, quirks, and natural geometry. The buildings buckled and bulged, and cobbles and stones were arrayed in a “disordered order”. Perfectly straight lines, which are almost absent in nature, were rare too in Gamla Stan. Instead, curved, crooked, and uneven geometry dominated. The buildings were also weathered by the passing of time which etched into their paint and stonework the imperfections and subtle variations that exposure to natural forces brings. Much like how a tree bear the scars of time in its snags, hollows, and creviced bark, so did the buildings of this city in their lop-sidedness, crookedness, and cracks. It was all immensely pleasing to the eye.

Then secondly, this is a city that takes pride in its appearance. The inhabitants of the place, and thankfully the town planners too, know they are stewards of something unique and incredibly special. Regulations now guard and manage what change can occur — keeping the intrusive forces of modernity at bay. Paintwork must be carried out according to the traditional style and the buildings themselves are protected by law. Streets have to remain cobbled, and any modern alternation should be made to conform aesthetically to the old appearance of the city as evidenced by the modern streetlights which look like gas lanterns. This pride of place allows Gamla Stan’s “inefficient and illogical6 beauty” to persist, which just goes to show what good can be achieved when local people take ownership of and have affection for the place they are in.

Pride is upheld because this place it is still a home, a home to three thousand people. It is a lived-in beauty. It is a place which pulsates with life, where history continues to be made by its inhabitants and the visitors they interact with. It is the opposite of what H.J. Massingham said concerning rural idylls, (which applies just as well to old cities): "Age withers the past when we try to keep it embalmed because it is the past. Our contact with the past can only remain living so long as it irradiates the present and teaches us the better how to live in it.".7

The past — through the multitudes of ancient buildings and the history and naturalness etched into their walls — irradiates the present in this special, unique place. It is a town that has retained its beauty, humaneness, and community in the face of immense pressures. Thus it is a living testament on how to design urban spaces more convivially and also how we can inhabit them better and more joyfully.

This essay is free, but any tips given (or paid subscriptions) support my work, help me to write more pieces, and are greatly received by this young writer.

Though the inhabitants of these “forsaken places” are among the most hospitable, beautiful people I have ever met.

Which roughly translates to The Old Town.

Stockholm translates to “log island”.

http://walkingstockholm.blogspot.com/2017/11/threats-to-stockholms-old-town-gamla.html

Rudberg’s comments as documented here: http://walkingstockholm.blogspot.com/2017/11/threats-to-stockholms-old-town-gamla.html

“Inefficient” in that vehicular traffic is inconvenienced, getting from a-b is far from simple in the irregular layout of the town, and old, inefficient ways of city life persist.Here one can see that inefficiency is not always a bad thing. “Illogical” that is to modern architects, health and safety bureaucrats, and modern town planners.

H.J. Massingham, Country.

If anyone asked: "why travel", the answer is here. Not to post a number of selfies on instagram, but to find what is essential to the area, what constitutes its beauty, and think how it can be preserved. Then, share an insightful narrative about the place.

I am not a keen traveller, not a perceptive one; and being aware of this, I've stopped travelling almost entirely. Having read this essay, I will perhaps remember more about Gamla Stan then if I took a glimpse of it on some hasty round trip.

I'm glad you enjoyed your visit to Stockholm, Hadden, and it's fascinating to see it through your eyes. If you find yourself in Sweden again, come and visit us: we're a local bus ride north of Uppsala, another old city that is worth seeing.

Sweden is a fascinating place to think about modernity. There was a rather good TV series a few years ago, made by a comedian who you could think of as the Swedish equivalent of Stephen Fry, the title of which translates as "The World's Most Modern Country". He was using the phrase only half-seriously, but it reflects an era in the 20th century when both at home and internationally the image of Sweden was of a country that lived closer to the future than anywhere else in the world. It's worth reflecting on the kind of cultural self-confidence that underwrites the Nobel prizes, where (among other things) a committee of Swedes adjudicates over the literature of the whole world.

The entanglement of Sweden with modernity has many threads: it's the country where Descartes came to die, where Linnaeus set about constructing a formal system to name and categorise all living things (including four subspecies of humans), and where a few generations later the world's first State Institute for Race Biology was founded to pursue eugenics research. The passing of the "Great Power Time" of the 17th century and the failure of attempts at establishing colonies further afield meant that Sweden could cultivate a sense of moral purity compared to the more successful colonial powers of Europe, though this rings hollow to the Sami people of the north.

I share your fondness for the earthy colours of the old paints – we're currently repainting the Red House, where I'm typing this, with a version of the classic Falu Rödfärg that you'll see all over rural Sweden. As you say, the colours do feel organic, part of the landscape. There's a darker element to this, too, in as much as the ubiquity of these colours reflects the origin of the paint as a byproduct of the mining of the landscape: industrial extraction began early here and continues on a huge scale. Linnaeus himself made a journey through the Bergslagen, the mining country to the west of where we live, and described the treeless ruin of the landscape, the smoking foundries and the condition of the people as resembling hell. It's one of those moments at which modernity caught sight of its own shadow.

The destructive modernisation of urban Sweden peaked in the 1950s and 60s, when many wooden neighbourhoods and city centres were bulldozed and replaced with modernised concrete. But this also provoked active resistance which led to the saving of some of what might have been destroyed and its protection in ways similar to what you've encountered in Gamla Stan, though the streets and buildings there are particularly special for the reasons you describe. Sigtuna is also worth a visit, as the central part of the town is still laid out on the same pattern as it was a thousand years ago, even if the individual wooden houses have been rebuilt at times along the way.

Finally, if you haven't come across it, I highly recommend Andrew Brown's Fishing in Utopia, a book that helped me find my bearings in my early years here and a fascinating read on the complex histories of this beautiful and strange country.