Quick reminder that next Saturday is another Wendell Berry Reading Group for paid subscribers. We will be discussing the essay The Agrarian Standard. More information and details for new participants can be found here.

Out on the expansive grazing marshes of Sligo Bay, a large flock of plump-looking creatures has congregated. Even from a distance you can clearly see they are covered in black and grey feathers and have stubby black beaks. To your eyes and mine, these creatures look unmistakably like birds: geese to be precise. However, according to medieval scholars and peasants alike, we could not be more mistaken. The creatures standing out there on the mudflats, according to their knowledge, are actually fish — and they are confident they can prove it.

If this sounds absurd (and it is) the story behind the curious case of the Fish Goose — or, as it is known now, the barnacle goose — is stranger still. It is a story of audacious claims, fabricated science, and, to top it all off, a papal injunction. Welcome to one of the strangest moments in natural history. A wild ride awaits.

Back in the Middle Ages, when superstition was part of everyday vernacular and when scientific research was still in its infancy, many natural phenomena whose explanations we now take for granted as common knowledge presented fearsome quandaries and deep mysteries to the medieval mind. Among the most troubling of these mysteries was ‘The Mystery of the Disappearing Geese’. During the winter, vast flocks of barnacle and brent geese took up residence on the estuaries and salt marshes of the west coast of Ireland and northern Britain. It was a welcome sight, for these geese provided a cornucopia of plump and delicious meat for squires and peasants alike. But in the springtime, the geese vanished; it was as if they had evaporated into thin air.

Such an abrupt exodus of a vital food source was a deeply perplexing, if not troubling, phenomenon — one that demanded an answer. No matter how spurious that answer may be.

One can surmise that some individuals, on the more scrupulous end of the religious spectrum, may have argued that the exodus was a portent of divine displeasure: a famine of meat stemming from the hand of God as punishment for some gross act of unrepentant national sin. There was though a critical problem with this explanation. For this to be so, the region and its citizens must regularly have been more sinful during spring and summer when the geese had vanished than in winter. This was highly unlikely as times of vice are not beholden to the seasons and climate; rather they arise from human hearts which can fall into gross sin at any time of the year. Divine displeasure could not be the reason. Another explanation needed to be found.

Others suggested that perhaps there was something unusual about these mysterious “birds”. Could there be something hidden in their life cycle that meant all through the summer they were hiding in plain sight, yet in a different form? What if these geese were in fact not birds at all. What if they were actually fish (or, more actually, shellfish) that only looked like birds later on in their lives?

Incredulous though this may sound to our modern ears trained in enlightenment rationalism and modern scientific advances, this explanation was entirely feasible to mystical medieval scholars and even to post-reformation naturalists. It made sense of the scant evidence that they had and was backed up by noble, and perhaps even royal, observation. More so, as we will come to see, this explanation was highly desirable — much vested interest was behind the perpetuation of this dubious zoological “fact”.

When this fanciful claim began is hotly contested, but there is one name that keeps popping up in association with this myth: Gerald of Wales (c. 1146 – c. 1223). Gerald was a well-travelled priest and a royal clerk to the king and his prestige and ability to travel gave him ample opportunity to engage in his passion for natural history. It appears, though, that Gerald had a fatal flaw in his zoological scholarship: he struggled to differentiate between fact and fiction. He also suffered from that great error of observation which has plagued naturalists down the ages: rather than letting his eyes see what was really there, his eyes were trained to see what he wanted to see.

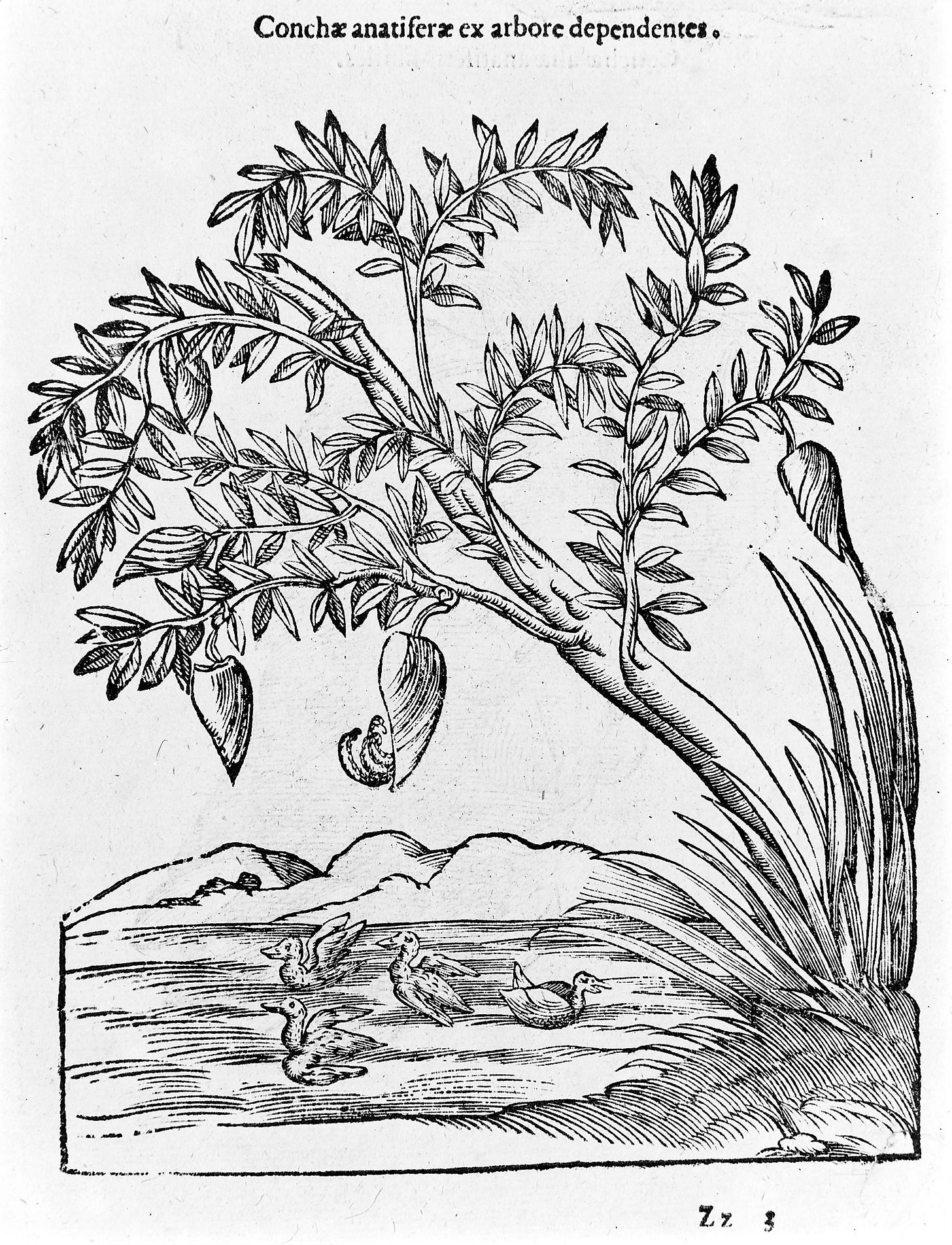

Chief among his fanciful claims and observations is this note on the barnacle goose — a myth that he is widely regarded as the chief propagator of: “I have often seen with my own eyes more than a thousand minute embryos of birds of this species on the seashore, hanging from one piece of timber, covered with shells, and, already formed.”

Others followed in Gerald’s footsteps, claiming they too had seen barnacle geese embryos in the shells of barnacles. Some went even as far as to claim to have found fully formed goslings within the shells when they opened them up.1 Perhaps they can be forgiven for some of their misinterpretation. With a degree of a rather vivid imagination, the goose barnacle does look a tiny little bit like a barnacle goose and the feathery fronds (called cirri), which the barnacle uses to feed, do look like feathers emerging from within. However, those unscrupulous individuals who claimed to have found living baby geese inside barnacle shells are guilty of gross fabrication; clearly this was a bare faced lie.

Of course, as Seton Gorden2 notes, the myth would have been dead in the water if the eggs of the barnacle goose had been located. Finding them, though, was an impossibility to all but the most adventurous explorers of the 12th Century, as the goose’s nesting grounds were as far away as Spitsbergen. Without access to any other contradicting evidence, goose barnacle (Lepas anatifera) became the definitive and widely accepted source of baby barnacle geese in the summertime. This was where they had been hiding all along. Mystery “solved”.

When it became the established “fact” that barnacle geese originated from barnacles, a fortuitous opportunity presented itself to the ever-industrious estuary dwelling folk. During Lent, eating meat was forbidden. Eating fish and shellfish meat, however, was permissible. Thus, if the barnacle goose began its life as a (shell)fish, then its fundamental nature is that of a fish; it only appears to look suspiciously like a bird later on in its life. Therefore, as the barnacle goose is actually a fish, goose (ahem, fish) meat was back on the menu during this lean period of fasting — a delicious proposition! And now, backed up by the latest cutting-edge scientific research, the estuary folk dined with liberty on goose (ahem, fish) meat to their hearts content.

Not everyone was convinced. This included the one individual no person in the Middle Ages would want to have standing in opposition to them: the Pope. Pope Innocent III was not best pleased by these Lent avoidance schemes and is reputed to have issued a Papal injunctions forbidding — in what could be said to be one the first example of species protection legislation — the consumption of Barnacle Geese during Lent. Wintering barnacle geese were given a 40-day long reprieve.

However, some folk believed the Pope has got his ornithology all wrong and were convinced that they should continue to be allowed to eat the geese (ahem, fish). Their eyes had seen the geese inside the barnacles, had they not? Of course they hadn’t, but appearances can be deceptive, especially when you are looking for what you already know what you want to see. Though the pope had delivered a crippling blow to the Barnacle Goose Myth, the blow was not yet fatal. The myth proved surprisingly persistent, continuing well on into the 18th century in isolated parts of the Irish coastal hinterlands.

Who would have thought this attractive little goose would be the source of so much controversy, lies, and devious schemes? It just goes to show how deceptive appearances can be.

Hector Bocae: “Alexander Galloway, parson of Kinkell, who, besides being a man of outstanding probity, is possessed of an unmatched zeal for studying wonders… When he was pulling up some driftwood and saw that seashells were clinging to it from one end to the other, he was surprised by the unusual nature of the thing, and, out of a zeal to understand it, opened them up, whereupon he was more amazed than ever, for within them he discovered, not sea creatures, but rather birds, of a size similar to the shells that contained them … small shells contained birds of a proportionately small size… So, he quickly ran to me, whom he knew to be gripped with a great curiosity for investigating suchlike matters and revealed the entire thing to me…” From Hector Boceae, "Scotorum Historiae a Prima Gentis Origine” (1574)

Seton Gordon (1987), Wild Birds of Britain. Batsford Books.

I’m planning to be at the Berry discussion group! Thanks for hosting!